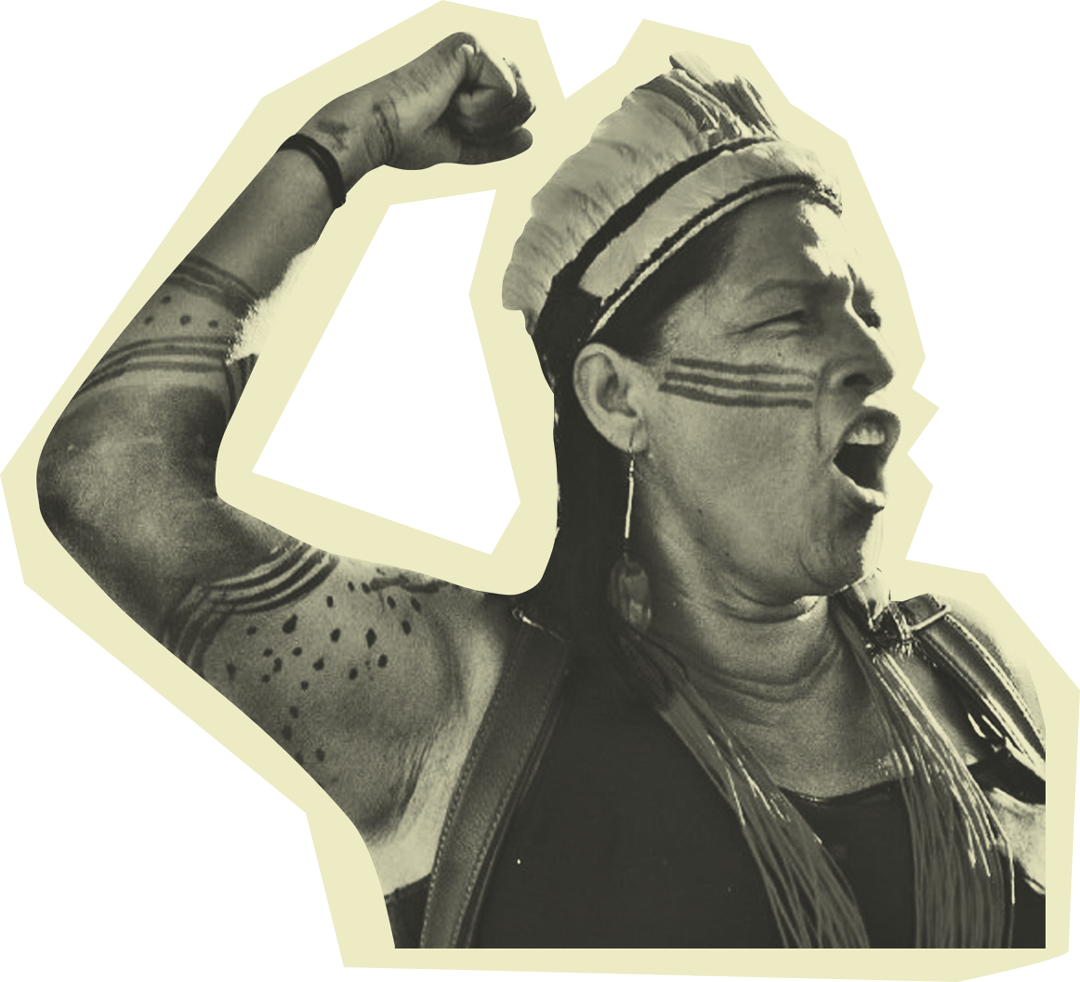

Indigenous Peoples defeat the Time Frame thesis! | STF overtunr the ruralist thesis by majority vote

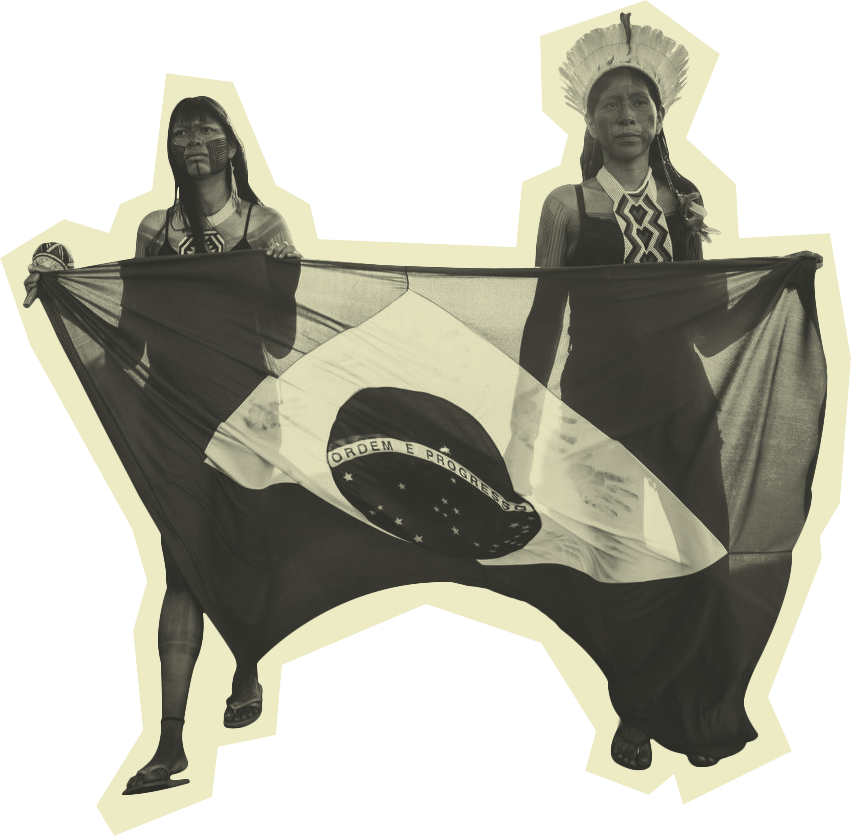

We stand firme! Rights cannot be negotiated!

Learn more about the Marco Temporal

Access the APIB booklet on the Marco Temporal and learn more about the thesis, the history of confrontation and the mobilization of the indigenous movement.

Follow on social media

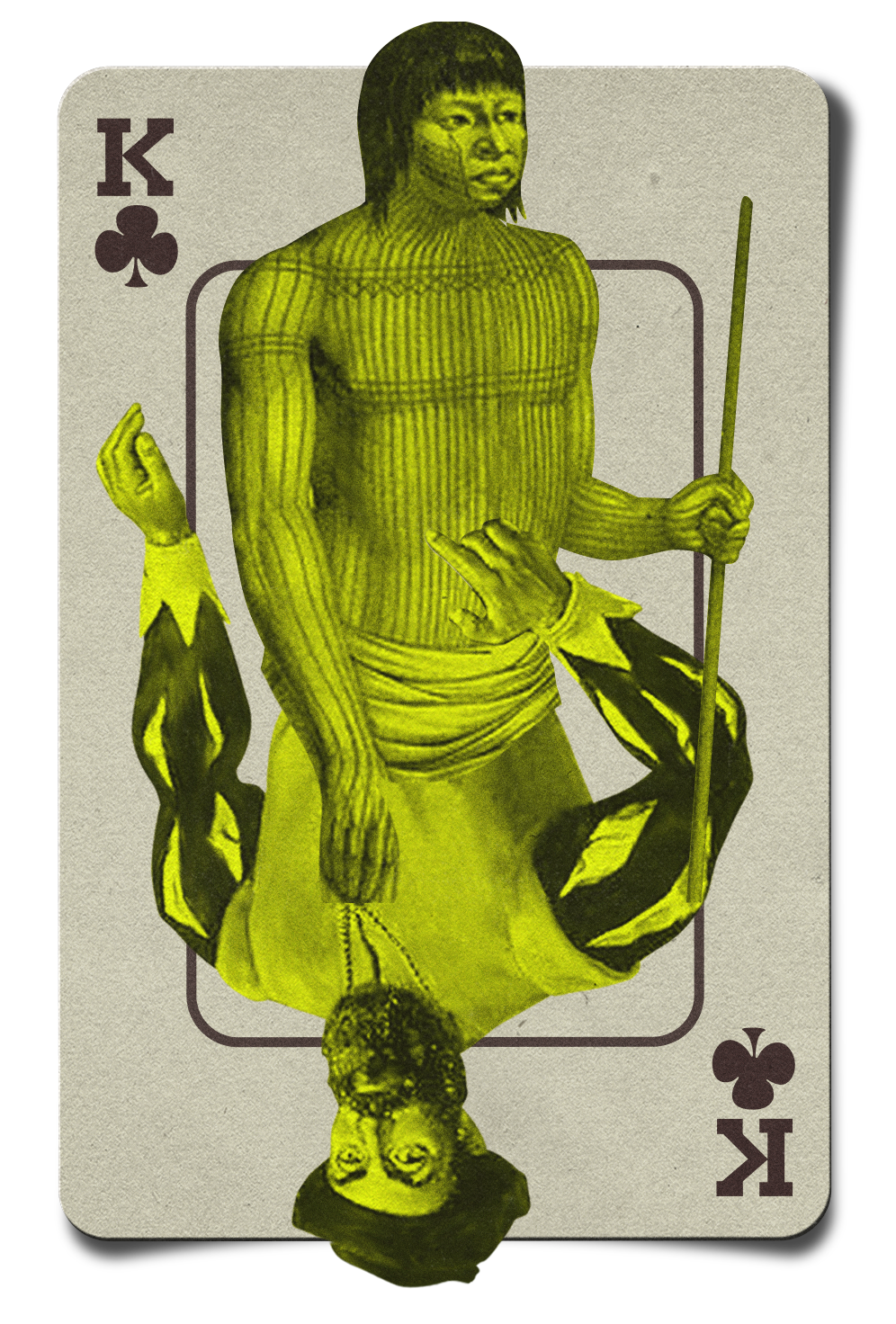

Voting score

Voting score

Understand Apib’s perspectives on the trial and the threat in Congress

We have indeed emerged victorious from the Time Frame thesis, but there is still much to be done to ward off all the threats that are also pending in the Senate, through the law proposal 2903. We remain mobilized, we continue to fight because we need to ensure and protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

Dinamam TuxáWe continue mobilised to ensure that no rights are negotiated!

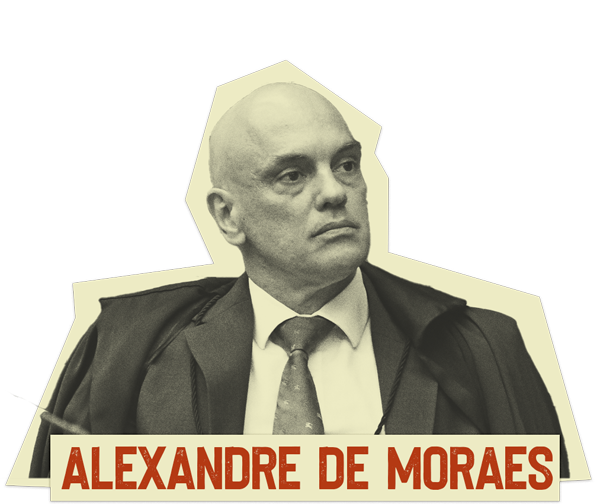

The Apib celebrates the victory on the Time Frame vote that recognises indigenous rights but warns that the mobilization continues because various indigenous lands are being invaded. “It is a victory for indigenous peoples because for years we have been fighting to reject this thesis that, in a way, was paralyzing the demarcation processes in Brazil. However, there are some important points to be noted because the votes of Toffoli and Moraes brought quite dangerous elements for Indigenous Peoples,” warns Tuxá. Even in a scenario with increasing violence caused by the illegal occupation of Indigenous territory, Minister Moraes raised the possibility of compensation for invaders who supposedly hold titles to rural property in “good faith,” and Toffoli defended the possibility of natural resources exploitation (water, organic, and mineral resources) located within Indigenous Lands.

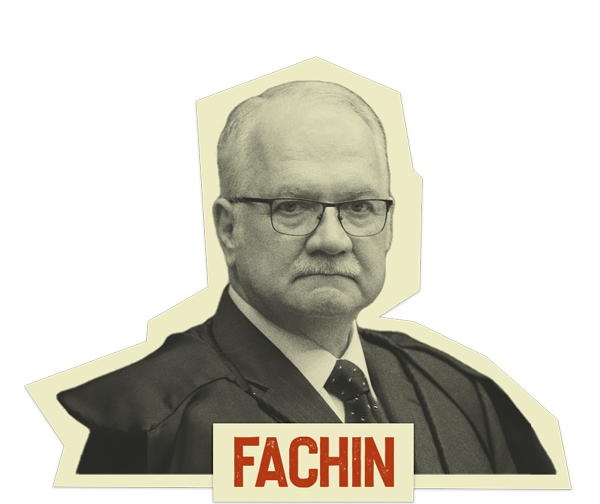

The ministers voting against the Time Frame thesis were: Edson Fachin, Alexandre de Moraes, Cristiano Zanin, Luís Roberto Barroso, Dias Toffoli, Luiz Fux, Cármen Lúcia, Gilmar Mendes, and Rosa Weber. André Mendonça and Nunes Marques voted in favor of the thesis.

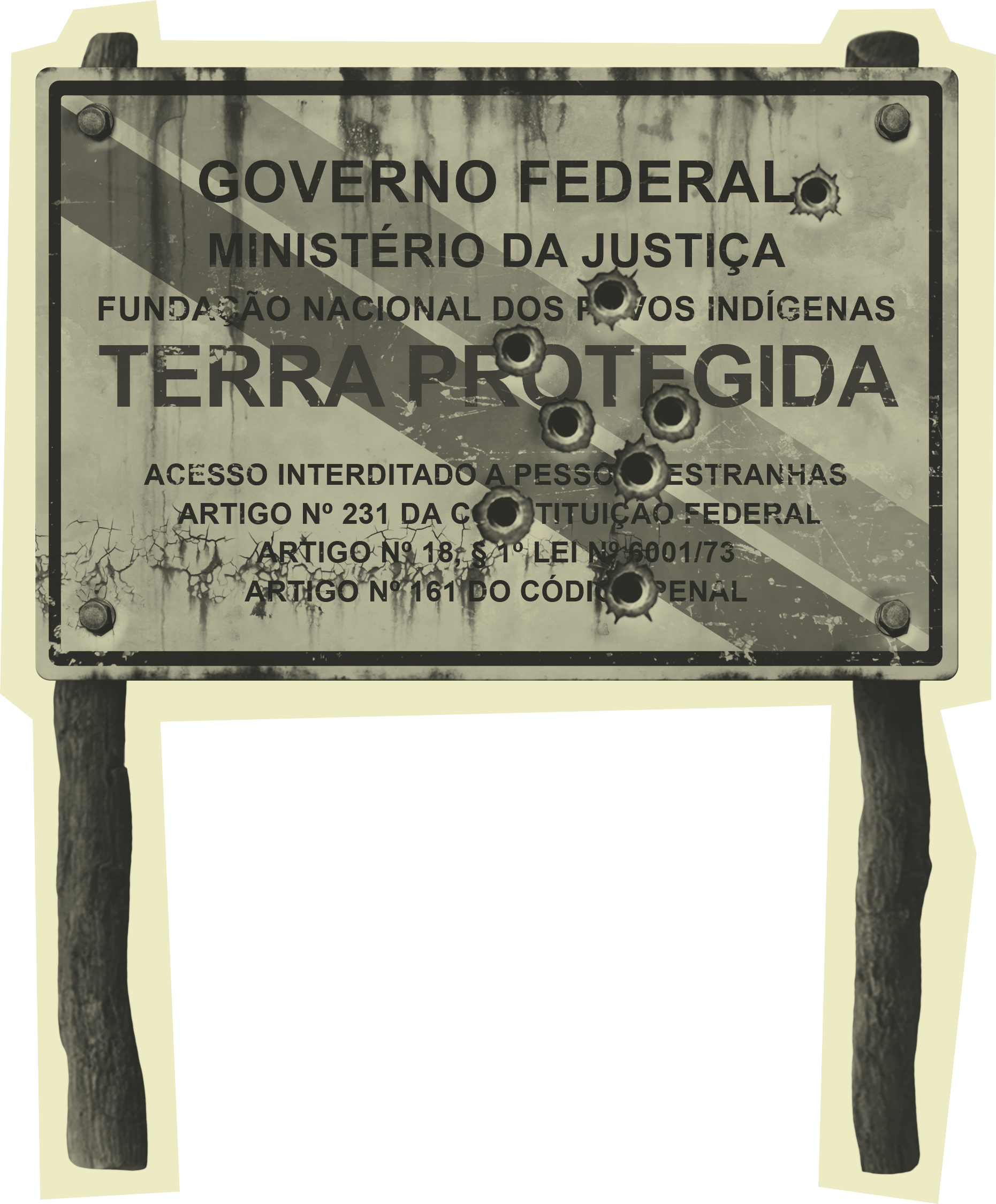

The Time Frame is a political thesis asserting that indigenous peoples would only have rights to their territories if they were in possession of them on October 5, 1988, the date of the promulgation of the Federal Constitution. Apib argues that the thesis is unconstitutional and anti-indigenous because it violates the original right of peoples to ancestral territory, as provided for in the Constitution itself, and ignores the violence and persecution, especially during the Brazilian military dictatorship, preventing many peoples from being on their lands on the 1988 date.

In the Supreme Court, the Time Frame refers to a possessory action (Extraordinary Appeal No. 1,017,365) involving the Xokleng Ibirama Laklaño Indigenous Land of the Xokleng, Kaingang, and Guarani peoples and the state of Santa Catarina. With the status of general repercussion, the decision in this case will serve as a guideline for all Indigenous land demarcation processes in the country. As Minister Luís Roberto Barroso stated, “the (Brazilian) Constitution is very clear, there is no ownership of land traditionally belonging to Indigenous communities. This is the solution to this case.”

Even though the result of the vote is a victory for the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, other proposals raised by the ministers in their votes threaten the current scenario of the fight for our rights.

Minister Alexandre de Moraes voted against the Time Frame in the Supreme Court session held on June 7, 2023. Despite his opposition to the thesis, he raised a highly threatening proposal for Indigenous Peoples. Moraes assumed the existence of rural landowners in “good faith” who could receive compensation from the State if they were to be expropriated from the illegally occupied lands for the demarcation as a indigenous land.

Apib considers that, despite the existence of a little portion of small landowners who acquired titles to Indigenous lands in “good faith” due to the illegality committed by the State, the compensation proposal assumes a reward for illegal invaders who represent the majority of properties with overlaps on Indigenous lands, thus incentivizing illegal land occupation paid with public funds. Based on the cross-referencing of land data from the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra) and the data from the “The Invaders” (Os Invasores) reports conducted by De Olho nos Ruralistas, there are 1,692 farm overlaps on Indigenous lands, totaling 1.18 million hectares, and out of this total, 95.5% are in territories pending demarcation. With his proposal, Moraes ignores the extensive history of land grabbing in Brazil and the criminal actions of ruralists, which have led to increased violence against Indigenous peoples and deforestation. Between 2008 and 2021, 46,900 hectares were deforested in areas of farm overlaps on Indigenous lands, according to the data from the aforementioned report.

On the other hand, Minister Dias Toffoli voted on September 20, representing the 5th vote against the Time Frame thesis. However, Toffoli chose to expand the topics with a theme unrelated to the one discussed in the case and included the possibility of exploiting water, organic, and mineral resources from Indigenous Lands, arguing that the issue suffers from a supposed legal omission and hinders the country’s economic development. Maurício Terena, legal coordinator of Apib, adds: “At the last moment, he (Toffoli) brought up an issue that concerns us greatly as an indigenous movement. He sets out theses on economic exploitation in indigenous lands. We understand that this is not the time for this debate, and the way he did it, to some extent, undermines the exclusive use of indigenous peoples.”

Who Benefits from the Time Frame thesis?

Among the threats, we highlight the illegal occupation of some Indigenous lands by certain farmers who are directly linked to the rural political power. Brazilian politicians, both in the National Congress and the executive branch, own 96,000 hectares of land overlapping Indigenous Lands. Furthermore, many of them were funded by farmers invading Indigenous lands, who donated R$ 3.6 million to the electoral campaign of ruralists. This group of invaders financed 29 political campaigns in 2022, totaling R$ 5,313,843.44. Out of this total, R$ 1,163,385.00 was directed to the defeated candidate, Jair Bolsonaro (PL).

Senate Vote Delayed

Under pressure from the ruralist caucus, the Senate Judiciary Committee had planned to begin debating the Law Project (PL) 2903 on September 20th, which aims to turn the Time Frame thesis into law and legalize crimes committed against Indigenous peoples. However, a lack of dialogue marked that day: Indigenous leaders were prevented from entering, and the Committee rejected a request for a public hearing. The vote was postponed to September 27th after a collective request for further examination by the senators. “The rights of Indigenous peoples are being violated, and we are not being heard. Parliament is not listening to public opinion, which only benefits the interests of agribusiness,” warns Tuxá. For the Apib, the clash between the legislative and judicial branches is an affront by politicians who want to impose their economic interests on Indigenous lands at the expense of Indigenous lives.

News about the Marco Temporal

30 dias de resistência: Povos Indígenas ocupam porto da Cargill contra privatização de rios amazônicos

Indígenas completam 30 dias de ocupação contra a transformação de rios ancestrais em corredores logísticos para o agronegócio.

“Nosso futuro não está à venda: a resposta somos nós” é tema do ATL 2026

A maior mobilização indígena do Brasil será realizada entre os dias 6 e 11 de abril, em Brasília (DF).

Carta política do Fórum Nacional de Lideranças Indígenas da APIB aos parentes no governo

Às parentas e aos parentes indígenas que hoje ocupam cargos no Governo Federal, e às autoridades responsáveis por decisões que impactam os povos indígenas.

NOSSO FUTURO NÃO ESTÁ À VENDA: A RESPOSTA SOMOS NÓS

Manifesto do Fórum Nacional de Lideranças Indígenas ao Estado Brasileiro

APIB’s POLITICAL STATEMENT ON THE EU-MERCOSUR TRADE AGREEMENT AND ITS IMPACT ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

January 26, 2026 The Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), the organization that represents nationally and internationally more than 300 indigenous peoples from all regions of Brazil, reaffirms its opposition to the signing and ratification of the...

Dia Nacional da Visibilidade Trans: Corpos e territórios em risco

Dossiê da ANTRA denuncia genocídio de indígenas trans e travestis e aponta que colonialidade, racismo e transfobia operam juntos na produção de morte, apagamento e violências contra corpos indígenas dissidentes.

“Nothing was given”: Indigenous mobilization assesses COP30 and projects decisive agenda for 2026

APIB’s assessment highlights historical achievements, but demands territorial ambition and binding mechanisms for the climate future.

COP30 Assessment by the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB)

IndexIntroduction: The Indigenous COP APIB highlights on COP30 Indigenous Participation at COP30EventsMarches and DemonstrationsPeople's SummitAchievements of the indigenous movement at COP30Progress in Demarcations and Land Protection at COP30COP30 Official...

APIB Public Statement to the Press

This edition of the COP is taking place in a democratic country, where the right to protest is guaranteed and respected, unlike previous editions held in more restrictive contexts. In this regard, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), together with...

In Belém, Pará’s capital, indigenous movement demands a legacy of land demarcation and territorial protection for COP30

APIB mobilizes over 3,000 indigenous people and proposes goals in conference negotiations.

Global voices unite in the campaign “The Answer Is Us” in an urgent call for climate justice and defense of life towards COP30

The official site of the “The Answer Is Us” campaign is now available.

APIB condemns acts of violence by anti-indigenous Congress

Photo: Richard Wera/Apib The Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) vehemently condemns the acts of violence by the anti-Indigenous Congress, carried out by the Legislative Police Department (DPOL) and the Military Police of the Federal District (PMDF) on...

Erasing the past and altering history in its entirety.

According to this legal thesis, there is no history prior to Oct 5, 1988, only after it.

It also flips the logic: those who were not in these lands are considered owners, while those who were present are labeled as invaders.

IT SEEMS AS IF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES WERE THE ONES WHO ARRIVED ON THE COLONIZER’S SHIPS.

It MANIPULATES history, placing the colonizer as the rightful landowner and Indigenous peoples as invaders.

The Marco Temporal denies the existence of Indigenous Peoples on these territories, and by denying our presence, it denies our contributions.

The Marco Temporal denies our survival strategies, rejects our scientific knowledge, our songs, our artwork, our cuisine.

It denies that for millennia, Indigenous Peoples were present protecting biodiversity,

denying the Indigenous contribution to the planet and their role in the history of this country so-called: Vera Cruz, Santa Cruz, Brazil that, in fact, could be PINDORAMA.

BESIDES BEING HARMFUL, THE Marco Temporal ERASES US FROM HISTORY

it resituates us in history, turns the bandit into the hero, and transforms the original inhabitants into evil beings who occupied and invaded other people’s lands.

This is the Marco Temporal (“Time Frame Thesis”), it truly limits our time. This machine goes back in time and reverses time, swapping people to a different time in order to erase memory and change history.

UNDERSTAND THE IMPORTANT POINTS OF THE MINISTERS’ VOTES

Civil vs. indigenous land ownership

- “At the outset, it should be stated that this Court has already ruled that indigenous possession differs from civil possession and is therefore not regulated by the privatization legislation in force, but rather by the constitutional provisions that configure indigenous territorial rights.”

- “In fact, civil possession can be conceptualized as “always a de facto power, which corresponds to the exercise of one of the faculties inherent to ownership” (GOMES, Orlando. Rights in rem. 19.ed. updated by Luiz Edson Fachin. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2004, p. 51)”

- “In the case of indigenous lands, the economic function of the land is linked to preserving the conditions of survival and the indigenous way of life, but it does not function as a commodity for these communities.”

- “Indigenous possession, therefore, is not the same as civil possession; it flows from the very formation of the identity of indigenous communities, and does not qualify as mere acquisition of the right to use the land.”

- “Land for indigenous people has no commercial value, as in the private sense of possession. It is a relationship of identity, spirituality and existence, and it can be said that there is no indigenous community without land, from an ethnic and cultural point of view, inherent to the very recognition of these communities as traditional and specific peoples in relation to the surrounding society.”

Native rights - fundamental indigenous rights, stone clause and prohibition of retrogression

- “To begin with, it should be stated that the rights of indigenous communities consist of fundamental rights, which guarantee the maintenance of the conditions of existence and a dignified life for indigenous people. By recognizing “their social organization, customs, languages, beliefs and traditions, and the original rights over the lands they traditionally occupy”, article 231 protects indigenous Brazilians’ individual and collective rights to be guaranteed by the Public Authorities through policies that preserve group identity and their way of life, culture and traditions.”

- “In the first place, the provisions of article 231 of the constitutional text are subject to the provisions of article 60, paragraph 4 of the Magna Carta, thus constituting a permanent clause to the action of the reforming constituent, which is prevented from promoting modifications tending to abolish or hinder the exercise of individual and collective rights emanating from the constitutional command.”

“Secondly, the rights emanating from article 231 of the CF/88, as fundamental rights, are immune from the decisions of eventual legislative majorities with the potential to curtail the exercise of these rights, since they consist of commitments signed by the original constituent, in addition to having been assumed by the Brazilian State before various international bodies (such as, for example, Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization and the United Nations Declaration on Indigenous Peoples). Therefore, they consist of enforceable obligations before the Public Administration, consisting of a structural duty to be performed by the State, and not merely conjunctural.” - “Thirdly, since they are fundamental rights, the prohibition of retrogression and the prohibition of deficient protection of their rights apply to indigenous rights, since they are linked to the very condition of existence and survival of the communities and their way of life.”

The native right to land is independent of demarcation

- “As can be seen from the constitutional text itself, the native territorial rights of the Indians are recognized, and therefore pre-exist the promulgation of the Constitution.”

- Therefore, the permanent possession of lands of traditional indigenous occupation is independent of the conclusion or even the completion of the administrative demarcation of these lands, it is the original right of the indigenous communities, being only recognized, but not constituted by the legal system. The legal nature of the demarcation procedure is merely declaratory, it consists of the externalization of the Union’s property, linked and affected to the specific function of serving as a habitat for the ethnic group that traditionally occupies it. It is an activity of the Executive Branch, carried out by various bodies, in accordance with the procedure shown above, but it does not create indigenous land, it merely recognizes those that are already, by native right, in the possession of that community.

Indigeneity theory vs. indigenous fact theory (Marco Temporal)

- “Indigenous rights over their lands are based on another source: Indigenato. The ‘traditionally’ refers not to a temporal circumstance, but to the traditional way in which the indigenous people occupy and use the land and the traditional way of production – in short, the traditional way in which they relate to the land, since there are more stable communities, others that are less stable, and those that have wider spaces through which they move, etc. Hence it is said that everything is done according to their uses, customs and traditions.” (SILVA, José Afonso da. Contextual Commentary on the Constitution. 8.ed. São Paulo: Malheiros, 2012, p. 889-890)”

- “The indigenous people’s right to possession and use of the land they occupied was not only not infringed by the aforementioned Land Law, but was also ensured by the provisions of article 24, paragraph 1 of Decree No. 1318/1854, which regulated said law, since it understood that possession was legitimized to the first occupant, and the indigenous people’s original right to the land in their possession was already recognized. This was, in the words of João Mendes Jr., the recognition of Indigenato, i.e. that the Indians were the first occupants of the land, and their possession was not subject to legitimization by the legal system, since it was not a question of acquiring a right, but merely of declaring its existence.”

- “Taking the issue from the normative aspect, and considering that the lands of indigenous occupation, at least from the legal perspective, were protected by the legal system and especially by the Constitutions since 1934, the “theory of indigenous fact” is not normatively justified, since I do not deduce from the Constitution any fracture in relation to the protection of indigenous territorial rights, since the simple appropriation of these lands by private individuals, encouraged or not by public entities, was never allowed by the constitutional texts.”

General Repercussion

- “The judge who analyzes this type of litigation, even if it is a process with an abbreviated rite, must first consider the elements that characterize indigenous possession, as stated in this vote: a) demarcation consists of a declaratory procedure of the original territorial right to possession of lands traditionally occupied by an indigenous community; b) traditional indigenous possession is distinct from civil possession, consisting of the occupation of lands permanently inhabited by the Indians, those used for their productive activities, those essential to the preservation of the environmental resources necessary for their well-being and those necessary for their physical and cultural reproduction, according to their uses, customs and traditions, under the terms of §1 of article 231 of the constitutional text; c) the date of the promulgation of the 1988 Constitution does not constitute a temporal milestone for the assessment of indigenous possessory rights, under penalty of disregarding these rights as fundamental rights, as well as the entire normative-constitutional framework for the protection of indigenous possession over time; d) the establishment of a legalized possessory claim on the date of the 1988 Constitution, or even of a persistent factual conflict on October 5, 1988, is not required for the demonstration of renitent encroachment; e) the anthropological report carried out under the terms of Decree no. 1. 776/1996 is a fundamental element for demonstrating the traditional nature of the occupation of a given indigenous community, in accordance with its uses, customs and traditions; f) the resizing of indigenous land is not prohibited in the event of non-compliance with the elements contained in article 231 of the Constitution of the Republic, by means of a demarcation procedure under the terms of the governing rules.”

- “Nevertheless, authorizing the loss of possession of traditional lands by an indigenous community, in contempt of the Constitution, means the progressive ethnocide of their culture, through the dispersion of the indigenous members of that group, in addition to throwing these people into a situation of misery and acculturation, denying them the right to identity and difference in relation to the way of life of the surrounding society, the greatest expression of the political pluralism established by article 1 of the constitutional text. There is no greater legal security than complying with the Constitution.”

The "alternative" proposal

- At first, Minister Alexandre de Morais presented a position contrary to the “Marco Temporal” thesis. However, he then presented an “alternative” proposal, with the aim of achieving a “conciliation”, which in practice diminishes the constitutional protection of the Original Right of Indigenous Peoples over their Lands of Traditional Occupation. The thesis put forward by Minister Alexandre de Moraes could guarantee the rights of rural producers and invaders in good faith. In other words, on the same occasion that Justice Alexandre de Moraes says he is opposed to the “Marco Temporal”, he presents two impediments that will make the demarcation of Indigenous Lands much more difficult, and will not solve the historical liability of land demarcations, much less bring social peace to the countryside.

The danger of "Prior Compensation"

The first impediment presented by Justice Alexandre de Moraes concerns prior indemnification for property title holders who are in good faith. In other words, even in cases where the rural producer’s property overlaps Indigenous Lands of recognized traditional occupation, if he can present a certificate of ownership of the Land registered with an official notary, he will be entitled to prior indemnification. Currently, this compensation is only for bona fide improvements. Justice Moraes innovates in his vote by stating that compensation should be for the bare land, i.e. the entire property.

In the analysis of APIB’s legal department, this proposal by Justice Alexandre de Moraes mitigates the Original Right of Indigenous Peoples to their Lands of Traditional Occupation, establishing new time frames according to the date on which the rural producer is able to present a certificate of ownership of the Land registered with an official notary. By removing paragraph 6 of art. 231 of the Federal Constitution, the Justice opens up the possibility for land grabbers to increase their activities on indigenous lands.

As for the specific issue of compensation, Art. 2313, §6 of Brazil’s Federal Constitution clearly states that purchase, sale and exploitation deals involving Indigenous Lands are invalid, null and void and do not give rise to the right to compensation.

In addition to the Original Right of Indigenous Peoples to their Lands of Traditional Occupation, which has been provided for in Brazilian legislation since at least 1680, the proposal violates the Constitutional Right of Indigenous Peoples to the Exclusive Usufruct of the resources existing on Indigenous Lands.

In proposing prior compensation, Minister Alexandre de Moraes confuses private possession protected by civil law with Traditional Indigenous Possession protected by the Federal Constitution. The fact is that private possession under civil law allows property to be parcelled out and negotiated, as well as expropriated by the Brazilian state in accordance with the “public interest”, upon prior payment of fair compensation. Traditional Indigenous Possession, on the other hand, is collective and must serve the well-being and physical and cultural reproduction of indigenous communities on a permanent basis. Furthermore, it is not possible to make Indigenous Lands available or sell them, since they have no commercial value and are not subject to any kind of expropriation, but rather demarcation, through the nullity and extinction of purchase, sale and exploitation deals involving Indigenous Lands, without the right to compensation.

Minister Alexandre de Moraes’ proposal does not take into account that until the 1988 Federal Constitution – which established the need for public tenders for registry agents – registry offices were “acquired” from the public authorities by private individuals, becoming a family asset that was then transferred to their children by inheritance, with little or no intervention from the state. It also fails to take into account the serious problem of land grabbing in Brazil, which consists of legalizing illegally acquired land, which, especially during periods of military dictatorship (but not only), occurred frequently, with the direct participation of the “owners” of notary offices.

"Passing a cat for a hare"

The second impediment concerns the possibility – according to the vague and generic expression of “public interest” – of the Brazilian state carrying out a “compensation of Lands to indigenous communities”, granting them lands elsewhere, which would supposedly be “lands equivalent to those traditionally occupied”;

Now, this proposal completely disregards the Indigenous Territorial Rights established in the Federal Constitution, as well as the relationship of Indigenous Peoples with their Original Lands, which are indispensable for the very maintenance of their customs, languages, traditions, identities and the conservation of their ways of life. In other words, the very survival of indigenous communities is closely linked to their territory of origin, so that it is a spiritual relationship and has nothing to do with the mere acquisition of the right to use the land.

A very worrying issue is that the court case that is judging the “Marco Temporal” aims to resolve a disagreement between the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples/Funai and the Environmental Institute of the government of Santa Catarina/SC, which claims a stretch of the Ibirama-La Klãnõ Indigenous Land inhabited by the Xokleng, Kaingang and Guarani Indigenous Peoples as an environmental protection area. As such, the proposal to compensate squatters in good faith is a totally foreign matter to the judicial process being judged. In other words, Justice Alexandre de Moraes is extrapolating the limits of the trial, since the divergence in judgment does not involve the indemnification of third parties in good faith.

It is important to highlight the position of Justice Edson Fachin, who was the Justice responsible for conducting the proceedings and who had direct contact with the evidence and documents produced throughout the judicial process. In a position of historic value, Edson Fachin made a correct interpretation of the Federal Constitution to recognize the integrality of the Fundamental Rights of Indigenous Peoples, whose Territorial Rights serve to guarantee the very Right to Exist, since without demarcated Land, there is no physical space where cultures, traditions and ways of life can be exercised.

Finally, we conclude that Minister Alexandre de Moraes’ proposal undermines the protection of Indigenous Constitutional Rights. Furthermore, it places the burden of bearing the historical mistakes made by the Brazilian state itself on Indigenous Peoples, insofar as the guarantee of the Fundamental Rights of Indigenous Peoples under their Lands of Traditional Occupation will now depend on the existence of financial resources on the part of the Brazilian state.

If the proposal made by Minister Alexandre de Moraes prevails, the Indigenous Peoples will “win, but not take”. Or, in popular parlance, it’s a case of “passing a cat for a hare”, since at the same time as Minister Alexandre de Moraes says he is opposed to the “Marco Temporal”, he presents impediments that will make the demarcation of Indigenous Lands very difficult.

SINCE 2021 FOLLOWING THE JUDGMENT ON THE MARCO TEMPORAL

ABOUT

THE MARCO

TEMPORAL

The future of Indigenous Lands is in the hands of the Supreme Court.

What is at stake?

The resumption of the trial of the Marco Temporal in the Supreme Federal Court, an anti-indigenous thesis that restricts the right of Indigenous peoples to the demarcation of their lands, is scheduled for June 7, 2023. The thesis, considered unconstitutional, states that Indigenous peoples would only be entitled to the demarcation of lands if they were in possession of them on October 5, 1988, the date of the promulgation of the Brazilian Constitution.

The ruling deals with a lawsuit involving the Xokleng Ibirama Laklaño Indigenous Land, of the Xokleng, Kaingang and Guarani peoples, and the state of Santa Catarina. Here you can understand a little more about the history, the Marco Temporal thesis and how the result of this trial, with general repercussion status, will guide all the indigenous land demarcation processes in the country.

The thesis

The Marco Temporal is a legal thesis that argues that Indigenous Peoples are only entitled to the demarcation of their traditional lands if they were occupying those lands on October 5, 1988, the date of the publication of Brazil’s Federal Constitution. According to this thesis, lands that were unoccupied or occupied by other people on that date cannot be demarcated as Indigenous lands. These territories can be considered the property of private individuals or of the State, and no longer of the original peoples who inhabit them.

The thesis has been defended by ruralist (pro-agribusiness) sectors and politicians contrary to the rights of indigenous peoples, who argue that the lack of a defined date for the occupation of lands by Indigenous people generates legal insecurity and land conflicts. However, this is widely criticized by jurists, indigenous organizations, social movements and environmentalists, who point out that the thesis is a step backwards for Indigenous Peoples’ rights and an affront to their dignity and survival. In addition, many indigenous communities were evicted from their lands during the military dictatorship and were only able to return after the date set by the thesis, which could result in serious violations of the human rights of these peoples.

Beginning of the discussion in the judiciary

Within the judiciary, the discussion about the Marco Temporal dates back to 2009, when the Raposa Serra do Sol case was decided (Petition 3.388). This ruling, while recognizing the demarcation of indigenous lands, imposed, in that specific case, a series of conditions called “institutional safeguards”, among them, the criterion of the Marco Temporal. Based on the conditions of this trial, a series of instruments were applied annulling the demarcation of Indigenous lands and ordering the eviction of entire communities.

In light of this, both the indigenous communities and organizations as well as the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Federal Public Ministry) appealed, seeking a new ruling from the Court, to define whether the conditions would automatically extend to other lands or not. The debate arose as to whether these “safeguards” or “19 conditions” should be followed in all the processes of demarcation of Indigenous lands until, in 2013, the Supreme Federal Court analyzed the appeals, deciding that the conditions of the Raposa Serra do Sol judgment “do not bind judges and courts when examining other processes relating to various indigenous lands (…). The decision is valid only for the land in question”. That did not prevent the argument from being used by parliamentarians and jurists who advocate for the interests of agribusiness and corporate capital.

Diante disso, tanto as comunidades e organizações indígenas quanto o Ministério Público Federal recorreram, buscando com isso, uma nova manifestação da Corte, para definir se as condicionantes se estendiam automaticamente às outras terras ou não. Instaurou-se o debate sobre se essas “salvaguardas” ou “19 condicionantes” deveriam ser seguidas em todos os processos de demarcação de terras indígenas, até que no ano de 2013, o STF analisou os recursos, decidindo que as condicionantes do julgamento Raposa Serra do Sol “não vincula juízes e tribunais quando do exame de outros processos relativos a terras indígenas diversas (…). A decisão vale apenas para a terra em questão”. O que não impediu que o argumento continuasse sendo utilizado por parlamentares e juristas que advogam para os interesses do agronegócio e do capital.

Michel Temer's Coup against Indigenous Rights

In 2016, with the coup against the Dilma government and the ascension of Michel Temer to the presidency of the republic, an accelerated rollback of the human rights of indigenous peoples in Brazil began. It was in this context that on July 20, 2017 the Official Gazette of the Union published Opinion n. 01/2017/GAB/CGU/AGU that obliged the Federal Public Administration to apply the 19 conditions that the Supreme Federal Court established in the Raposa Serra do Sol case, institutionalizing the Marco Temporal thesis.

The effects were extremely negative. Immediately Funai began to review various procedures for demarcation of Indigenous lands throughout the country, and even processes that were already in an advanced stage at the Civil House and Ministry of Justice were returned to Funai to be re-examined. Without a doubt, this Opinion drawn up by the ruralist sector during Michel Temer’s government has brought serious consequences to the rights and interests of Indigenous Peoples. This Opinion was issued at the very moment when Michel Temer needed the support of the pro-agribusiness rural caucus to prevent the admission of charges against him in the Brazilian Congress. APIB even filed a complaint with the Attorney General’s Office, but the case was dismissed.

The Xokleng case and the General Repercussion

The Extraordinary Appeal with general repercussion (RE-RG) 1.017.365, which is on the agenda of the Supreme Federal Court (STF), is a repossession suit filed by the Environmental Institute of Santa Catarina (IMA) against the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) and the Xokleng Indigenous people, involving an area claimed to be part of the Ibirama-Laklanõ Indigenous Land. The disputed territory was reduced throughout the 20th century and the Indigenous people have never stopped claiming it. The area has already been identified by Funai’s anthropological studies and declared by the Ministry of Justice as part of their traditional land.

general repercussion

Extraordinary Appeal with General Repercussion is a type of appeal that, once its general repercussion is recognized by the Supreme Federal Court (STF), has its effects extended to all similar cases proceeding in the lower courts of the Judiciary. In a decision published on April 11, 2019, the STF plenary unanimously recognized the general repercussion of the trial of RE 1.017.365. This means that what is judged in that case will serve to fix a thesis of reference for all cases involving Indigenous lands, in all instances of the judiciary.

repercussion in the legislative

There are many cases of land demarcation and tenure disputes over traditional lands that are currently judicialized. There are also many legislative measures that aim to remove or relativize the constitutional rights of Indigenous Peoples. By admitting the general repercussion, the STF also recognizes that there is a need for a definition on the subject.

the STF

The Supreme Federal Court is the apex body of the Judiciary, and it is responsible for safeguarding the Constitution, as defined in art. 102 of the Constitution of the Republic. It is composed of eleven Ministers, and appointed by the President of the Republic, after approval of the choice by an absolute majority of the Federal Senate. Learn about the voting dynamics and expectations of the process by accessing the Voting Panel on the APIB website.

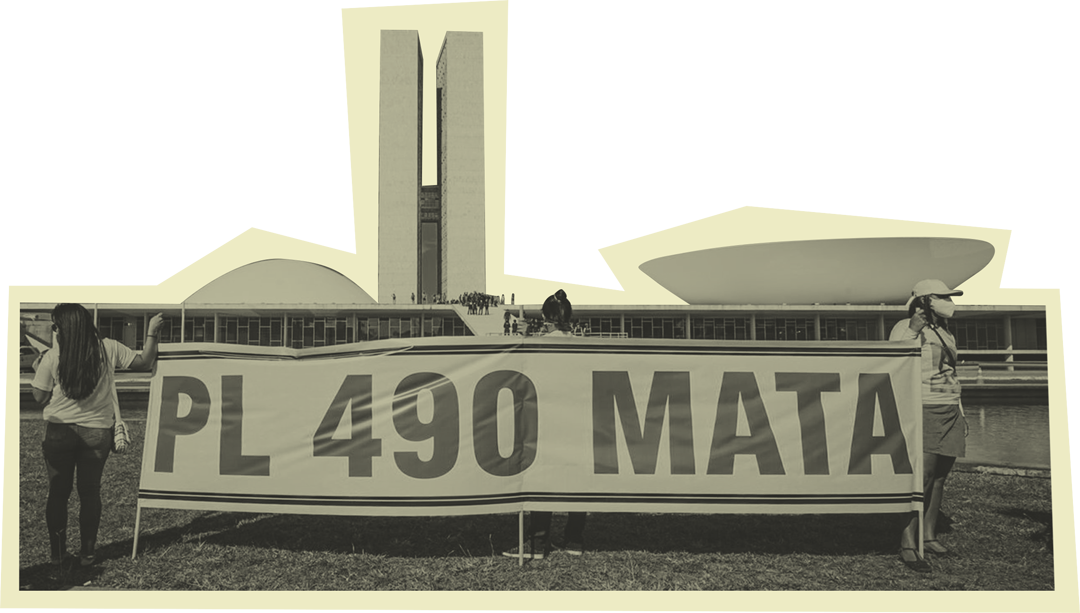

Congress Alert: Beginning of the legislative discussion

In the legislative sphere, it is important to mention the Bill (PL) 490/2007 (Dep. Homero Pereira), which aims to alter the “Statute of the Indian” (Law n° 6.001/1973) by proposing that Indigenous lands be demarcated by law, that is, that the demarcation pass through legislative approval (through the National Congress). On May 15, 2018, Rep. Jerônimo Goergen presented an Opinion to the Constitution, Justice and Citizenship Commission, proposing the establishment of the Marco Temporal through legislation. Also in the discussions of PEC 215/2000, parliamentarians repeatedly used the argument of the Marco Temporal to command support for the approval of this proposal. Such actions are a clear attempt by the rural caucus to try to implement the Marco Temporal by legislative means.

Legal technical note

Technical note from Apib’s legal sector on Bill 490. Access here

PEC 215/2000

PEC 215/2000 consisted of a proposal for an amendment to the Brazilian Constitution that aims to transfer the competence for the demarcation of Indigenous lands from the Executive Branch to the National Congress. In other words, PEC 215 proposes that the demarcation of Indigenous lands be made by means of a bill to be approved by Congress, instead of being an exclusive attribution of the Executive Branch, as it is currently. At present the proposal has been dropped, however, PEC 156/2003, which was attached to 215, is now being dealt with separately, and there are several others attached, many of them with the same content as the PEC.

Original right

INDIGENOUS PEOPLE LIVE UNDER THE LAW OF NON-INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, BUT ALL LIVE ON OUR LANDS.

Theory of Indigenato

The theory of Indigenato was developed by João Mendes Junior. This theory expresses the concept of Indigenato as being an original right, prior to the State itself and prior to any other right. In the words of Professor José Afonso da Silva: “The Indigenato is the primary and inherent source of territorial possession; it is an innate right, while occupation is an acquired right. Indigenato is legitimate in itself, it is not a fact which depends on legitimization, while occupation, as a subsequent event, depends on conditions that legitimize it”. In this sense, the 1988 Constitution adopted the Indigenato theory when it recognized the Indigenous Peoples’ original right to traditionally occupied lands. In a recent trial that took place on August 16, 2017, the STF discussed the issue and in the votes it is possible to extract important points that make it clear that the Indigenato doctrine has Constitutional validity.

The 1988 Constitution adopted the Theory of Indigenato by recognizing the Indigenous Peoples’ original right to traditionally occupied lands.

Original right under legal frameworks

Between 1600 and 1700 original rights were already translated into legal frameworks. The charter of April 1 dates from 1680, which states “The natives … are masters of their farms [in the villages] as they are in the countryside, without being able to be taken from them […] right of the Indians, primary and natural masters of them […]”. Moreover, in 1686 the Regiment of the Missions, decreed by Pedro II, King of Portugal, guaranteed indigenous peoples the right to refuse to leave their lands.

More recently, the Federal Constitution of 1988, still in force today, in Chapter VIII – Indians, Article 231, recognizes indigenous peoples’ original rights over the lands they traditionally occupy. Indigenous lands, according to the text, are those inhabited on a permanent basis, used for productive activities, indispensable for the preservation of the environmental resources necessary for the well-being of their occupants, and necessary for their physical and cultural reproduction, according to their uses, customs, and traditions. Indigenous peoples have exclusive possession and usage of these lands, which are inalienable, and cannot be removed from them except in cases of exceptional risk – and must return as soon as the risk ceases, according to the text.

In 1989, the International Labor Organization’s Convention 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples was published. Today, this is the main international convention concerning indigenous peoples. It states that indigenous peoples must be consulted in initiatives and projects concerning their lands.

These are just some of the historical legal frameworks regarding indigenous rights.

Impacts of

the Marco Temporal

Who is interested in the Marco Temporal?

Agribusiness

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

The thesis of the Marco Temporal (“Time Frame”) was practically ordered by the rural sector which, with great economic influence, has managed over the years to increase its bench in the National Congress and take on an anti-rights role regarding the demarcation of indigenous and quilombola lands. The sector has as its policy the conversion of the environment into commodities for capital and entities linked to agribusiness.

Exploitation of natural resources

Much of the lobbying and mobilization in favor of the Marco Temporal claims that the demarcation of Indigenous lands interferes with individual rights and issues related to national security policy on borderlands, environmental policy and matters of interest to the States of the Federation and others related to the exploitation of water and mineral resources.

Gold mining

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

Here we highlight the exploitation of the Yanomami, Munduruku and Kayapó Indigenous Lands directly affected by illegal mining in recent years.

Impacts on Indigenous Lands and for the World

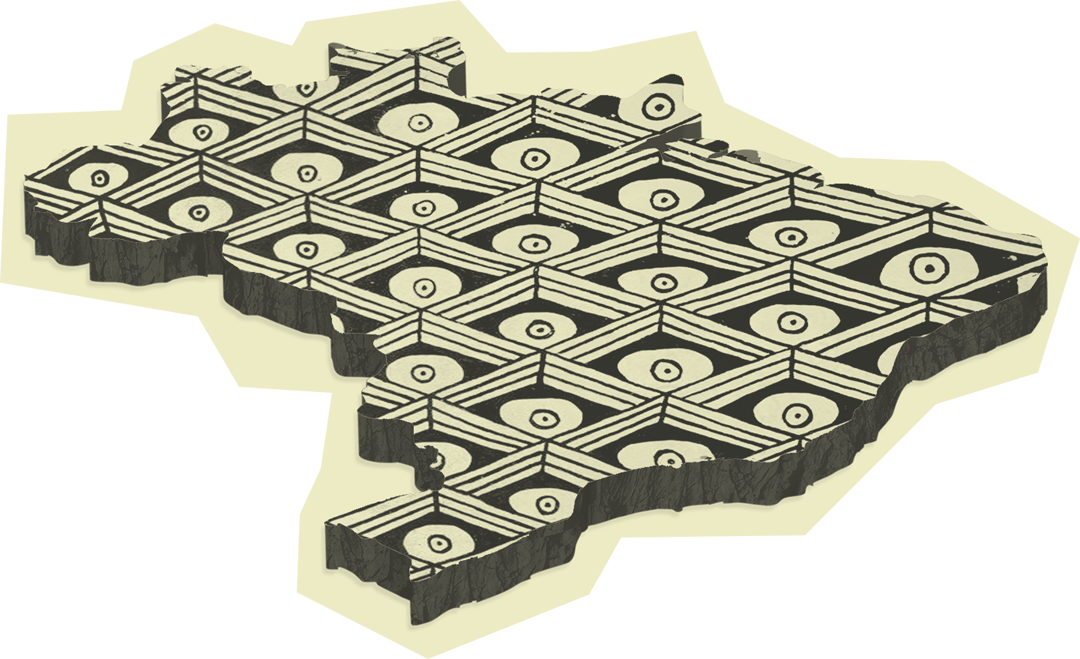

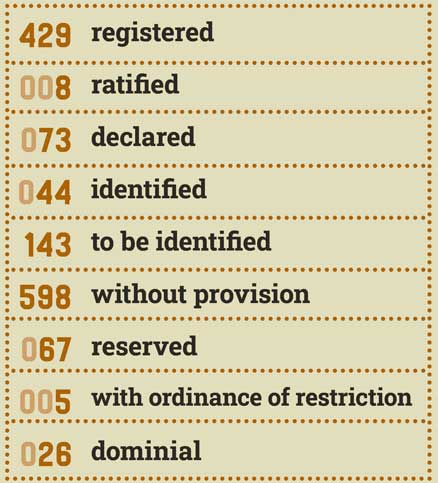

If the Marco Temporal is approved, all Indigenous Lands, regardless of their status and region, will be evaluated according to the thesis, putting all 1393 Indigenous Lands under direct threat.

FONTE:

Relatório Violência Contra

os Povos Indígenas no Brasil

Dados de 2021, CIMI

Isolated peoples

The isolated and recently-contacted peoples of Brazil are directly threatened if the ruling is unfavorable. This is because, in many cases, it would be difficult or even impossible to prove the presence of these groups on October 5, 1988 on the lands where they live today, which would make the demarcation of their territories unviable. To this day, the Brazilian State ignores the existence of these communities. It is not reasonable to demand that, on a specific date, these people were formally claiming the recognition and regularization of their territories.

On the other hand, proving that they were in a situation of deflated conflict is not an easy task either, in view of the persecution and concealment of signs of their presence by invaders and the omission of the State in protecting them. Of the 115 records of the presence of isolated indigenous groups in Brazil, 86 have yet to be confirmed – that is to say, if their existence is confirmed, it is still not clear what territory these groups have traditionally occupied.

Indigenous Peoples and their Lands preserve the future of humanity

Scientists around the world continue to demonstrate how the lands traditionally occupied by Indigenous Peoples are the areas with the greatest biodiversity and best-preserved vegetation. In other words, demarcating Indigenous Lands and keeping them protected from illegal invaders, miners, loggers, and the advance of agribusiness is to guarantee that the carbon stock in this area is preserved and the rights of Indigenous Peoples respected.

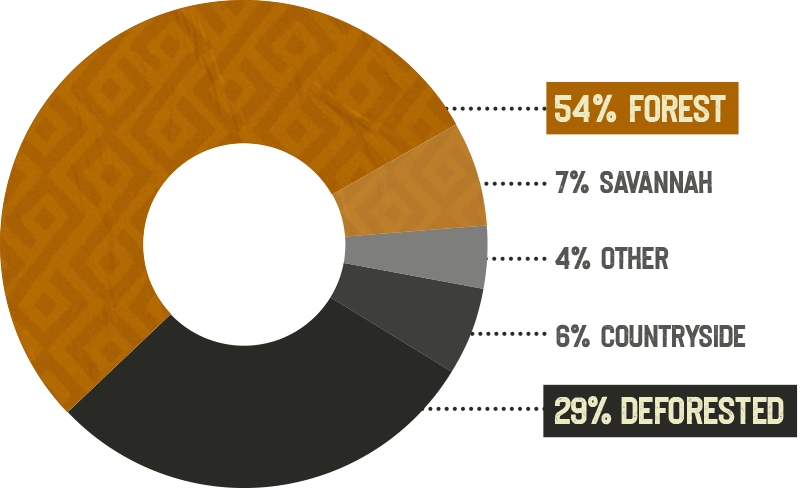

The mapping shows that most of the deforested areas are destined for pastureland for raising cattle (for meat and leather export) and the production of soybeans, but also highlight sugarcane, rice, eucalyptus or cotton plantations, among other commodities.

FONTE:

IPAM e APIB com dados MapBiomas Coleção 7

e base de dados de terras indígenas da Funai.

Analysis made by Apib and IPAM, with data from MapBiomas, show that 29% of the territory around Indigenous Lands in Brazil is devastated, while inside the Indigenous Lands there is only 2% deforestation.

Congress Alert

BILL 490/2007 AND BILL 2903/2023 - MARCO TEMPORAL

Establishes that Indigenous Lands will be demarcated through legislation. It seeks to reverse the constitutional protections for Indigenous Lands.

BILL 191/2020 - GENERAL EXPLOITATION

Aims to allow industrial and artisanal mining, hydroelectric generation, oil and gas exploration, and large-scale agriculture on Indigenous Lands, removing these communities’ veto power over decisions that impact their lands.

BILL 2633/2020 AND BILL 510/2021 - LAND GRABBING

Although the ruralist bench tries to argue that the projects will be beneficial to small producers, neither bill brings benefits to fight land grabbing and deforestation, they increase the risk of regularizing areas which are in conflict and encourage the continued invasion of public lands.

BILL 3729/2004 (NOW IN THE SENATE AS BILL No. 2159/2021) - ENVIRONMENTAL LICENSING

This bill, together with Bill 2633/2020 and Bill 510/2021, weakens the requirements for environmental licensing and allows “self-licensing” for a series of projects. If approved, it could result in the proliferation of tragedies such as those caused by mining that occurred in Mariana and Brumadinho (MG), in the total lack of containment of all forms of pollution, with serious damage to the health and to society’s quality of life, in the collapse of the water supply, and in the destruction of the Amazon and other biomes.

BILL 177/2021 (WITHDRAWAL OF ILO CONVENTION 169)

Aims to withdraw Brazil from Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, the main instrument of international law for the protection of Indigenous rights. The argument is that Brazilian legislation in this area does not need to be complemented by an international standard. It also claims that the restrictions established by the Convention on State action in the territories of these peoples make Brazil’s economic growth unviable.

History of mobilizations

While Indigenous lives and territories are threatened with extinction, Indigenous peoples continue to resist. Here are some of the mobilizations called for recently:

Struggle for Life

Rise for the Earth

When a government was more dangerous than a virus, Indigenous Peoples could not remain silent. Thus, in the face of a Congress that advanced an anti-indigenous agenda and to mobilize against the Marco Temporal, the Indigenous peoples, the first on this land, headed to the federal capital in June 2021, sounding their maracas and chanting their songs, with the Rise for the Earth.

The Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib) began the Struggle for Life camp in Brasilia on August 22, and strengthened the mobilization until September 2, 2021 to fight for Indigenous rights. The mobilization Struggle for Life reinforced the rallying cry: “Our history does not begin in 1988!”

Mobilization guide

Support and defend the original rights of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil and join the mobilization against the Marco Temporal.

You can support in different ways:

In the territories

In your village, community, territory, municipality or state, you can organize and hold protests against the Marco Temporal. Produce posters, banners and rallying cries with the words “No Marco Temporal”, “Demarcation Now” and “No more genocide”, for example. Don’t forget to also hold conversations, assemblies, and exhibitions.

Use this and other APIB materials as a basis for your debates, tag @apiboficial on social networks and share your mobilization with us!

On social networks

Make photos, videos and texts about the importance of defeating the Marco Temporal thesis.

You can tell or invite a leader to talk about how the thesis can impact your territory and the lives of indigenous peoples.

Do not forget to tag the Association of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (@apiboficial)

and / or its regional organizations.

@apoinme_brasil

@coiabamazonia

@arpinsuloficial

@cons.terena

@atyguasu

@yvyrupa.cgy

@arpinsudestesprj

Before confirming the publication of the material, be sure to include tags. They are important for the content to reach more people!

Check out some suggestions:

#MarcoTemporalNão!

#ParecerAntidemarcaçãoNão!

#Parecer001Não!

#VidasIndígenasImportam

#NossoDireitoÉOriginário

#IsoladosEmRisco

#Muitaterraprapoucofazendeiro

#Muitaterraparapoucolati

Download and share the materials

Identidade visual | Visual identity

Cartilha | Booklet

Card

Release de imprensa | Press Release

Noticías | News

Tuitaço | Tweetstorm

Videos

Access Apib’s content channels

MOBILIZAÇãO INDÍGENA

ATL